This article was created in partnership with Japanese Film Festival Australia. The festival will tour nationally from October – December 2019. For more information, visit the festival website.

It’s rather fitting that the English title of Masaaki Yuasa’s latest film, screening at this year’s Japanese Film Festival – Australia, is called Ride Your Wave. Because Yuasa, the most unpredictable, ambitious, and idiosyncratic figure in animation today, has made a career and reputation out of being on no one’s wavelength but his own.

Yuasa’s career began in the early 1990s, when he started working for animation studio Asia-dō on its family-friendly series Chibi Maruko-chan. He would move from there to work on the long running Crayon Shin-chan series for Shin-Ei Animation (Yuasa – returning to his roots – is currently directing a spinoff series, Super Shiro, based on the family dog). It was there that Yuasa first got experience directing, handling a number of episodes and specials. In a career spanning talk in Dortmund, Germany, in 2011, Yuasa praised Shin-chan series director Mitsuru Hongo for giving him the freedom to animate whatever his imagination could materialise; it was Yuasa’s first taste of creative independence working in the anime industry, something that he has held onto ever since.

He would move on to freelancing, gaining experience in just about every aspect of anime production; doing storyboards, animation, character designs, and even screenwriting. During that time, he got to work alongside anime legends like Kōji Morimoto (Robot Carnival, The Animatrix), and Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya), before branching out to make his debut feature film, Mind Game.

It isn’t surprising that many didn’t know what to make of Mind Game when the film hit Japanese theatres 15 years ago. The films plot – which follows a 20 year old loser named Nishi, who after rescuing his childhood love interest Myon from a hot headed soccer player (being killed and resurrected in the process), ends up getting them both (along with Myon’s sister Yan) swallowed up by a whale after a high speed car chase – moves at a frantic, exhilarating pace; Yuasa barely concerned with it making any kind of narrative sense. Its visual presentation — a mixture of traditional 2D animation, CG, rotoscoping, live-action footage, and paper animation — was also unlike anything anime fans who grew up on Hayao Miyazaki, Mamoru Oshii, or anything playing on television at the time, were accustomed to seeing.

It was too experimental and too radical for a commercial audience, so it was mostly ignored at the Japanese box office. However, it quickly became a cult classic among animation enthusiasts, and even won awards over Miyazaki’s more traditional and successful 2004 film, Howl’s Moving Castle.

Still from ‘The Tatami Galaxy’.

Stretching the Boundaries of TV Anime

It would take 13 years before Yuasa would get another opportunity to direct a feature film. In that time, he directed a number of anime series and shorts that would further expand on his reputation as a radical outlier in the industry.

There was his first TV anime, 2006’s Kemonozume, a love story about star-crossed lovers; one being a shape shifting, flesh eating monster, the other a human coming from a family whose sole purpose is to hunt and kill those monsters. In 2008, he directed the short, Happy Machine, part of the Genius Party anthology film, where an infant discovers that the world he knows is illegitimate. That same year, he also made his second series, Kaiba; a science-fiction story that looks like if you took characters from the earliest days of Japanese TV anime, and placed them in the kind of gloomy, oppressed world found in the novels of Phillip K. Dick.

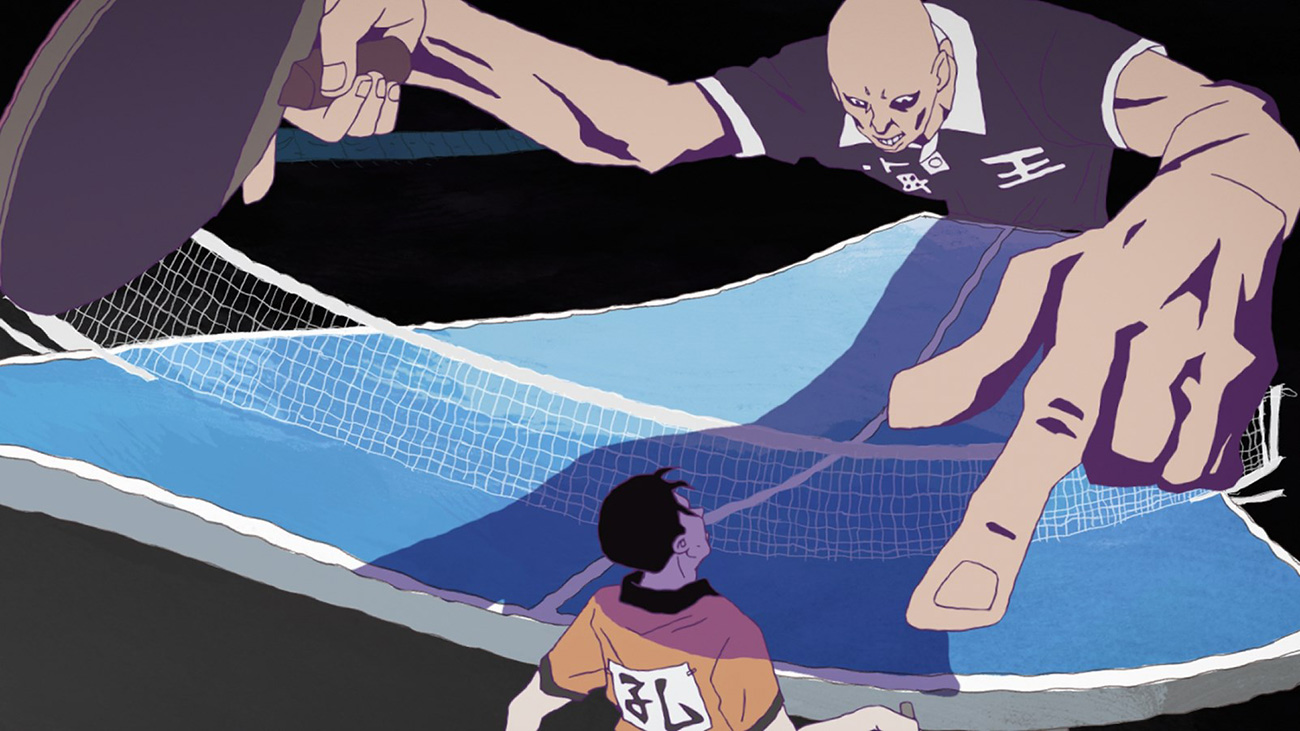

In 2010, Yuasa helmed the first crowdfunded anime project, the 12-minute short Kick Heart, a kinky, masochistic love story between two masked luchadores, and The Tatami Galaxy; a coming-of-age comedy where a college freshman tries to figure out how to have the idyllic college experience. Four years later, Yuasa went into sports with Ping Pong: The Animation, an anime focused around a handful of elite ping pong players who not only have to compete against one another on the table but also overcome something even more challenging than a quick serve: adolescence.

During this time, he still worked as a freelancer, doing key animation for Sayo Yamamoto’s Lupin the Third: A Woman Called Fujiko Mine, Shinichiro Watanabe’s Space Dandy, and one particularly memorable episode of Pendleton Ward’s Adventure Time.

What separated Yuasa from so many TV anime creators is that every series or short that had Yuasa’s name attached to it, whether it was an original story or an adaptation, had his imprint in many aspects of the production. He not only served as series director on all his TV anime, but he storyboarded and directed many individual episodes. For Galaxy and Ping Pong, he also went as far as to write or co-write the scripts for the entire series. All of this is extremely rare in the heavily collaborative environment of TV anime. The series’ were all also, like Mind Game, both visually and narratively detached from just about anything being produced at the time.

In that same 2011 talk in Germany, Yuasa expressed the hardships that come with making TV anime: “[T]here is a lot of pressure for the characters to be kawaii [cute] and for the story to be easily understood.”

Still from ‘Ping Pong’.

While simplistic (with the exception of some of the characters in Kaiba and Galaxy), Yuasa didn’t design characters that were visually pleasing, clean, adorable; the kind anyone with even the slightest experience with anime would be familiar with. Some of his designs were crude, sometimes deliberately off-model, at times, just plain off putting. As simplistic as his designs would be, Yuasa’s characters were all complicated individuals with unique personalities. How he pulled that off was that he would emphasise their emotions or mental states by allowing their faces and bodies to change, morph, and sometimes undergo extreme transformations.

Yuasa has been very upfront about the influence American animation icon Tex Avery had on his style of animation. Avery’s directorial work with Warner Bros. was filled with gags that had characters over-exaggerate everything from fear to joy to lust.

You see it in Kick Heart, when steam starts to spurt out of Masked Man X’s nipples, as he experiences both intense pain and pleasure thanks to the submission hold placed on him by Lady S. In the first episode of The Tatami Galaxy, the main character’s usually snow-white body turns from white to pink to darker shades of red the more alcohol he drinks, and in Ping-Pong, we see a player’s body grow to immense size, symbolising his immense confidence and utter dominance the character has over his opponent across the table.

Another aspect of his TV work that quickly separated him from practically everyone in the industry, was the variety of his stories. Kemonozume is a romance with a tinge of horror, Kaiba is a science-fiction mystery, Galaxy is a coming-of-age comedy, and Ping Pong is an action-sports drama (all done in flash no less). No two Yuasa series are alike in terms of tone, genre, or visuals. His insistence on not being tied down to a particular genre or style makes him more in line with live-action directors like Sion Sono, rather than his contemporaries, like Makoto Shinkai.

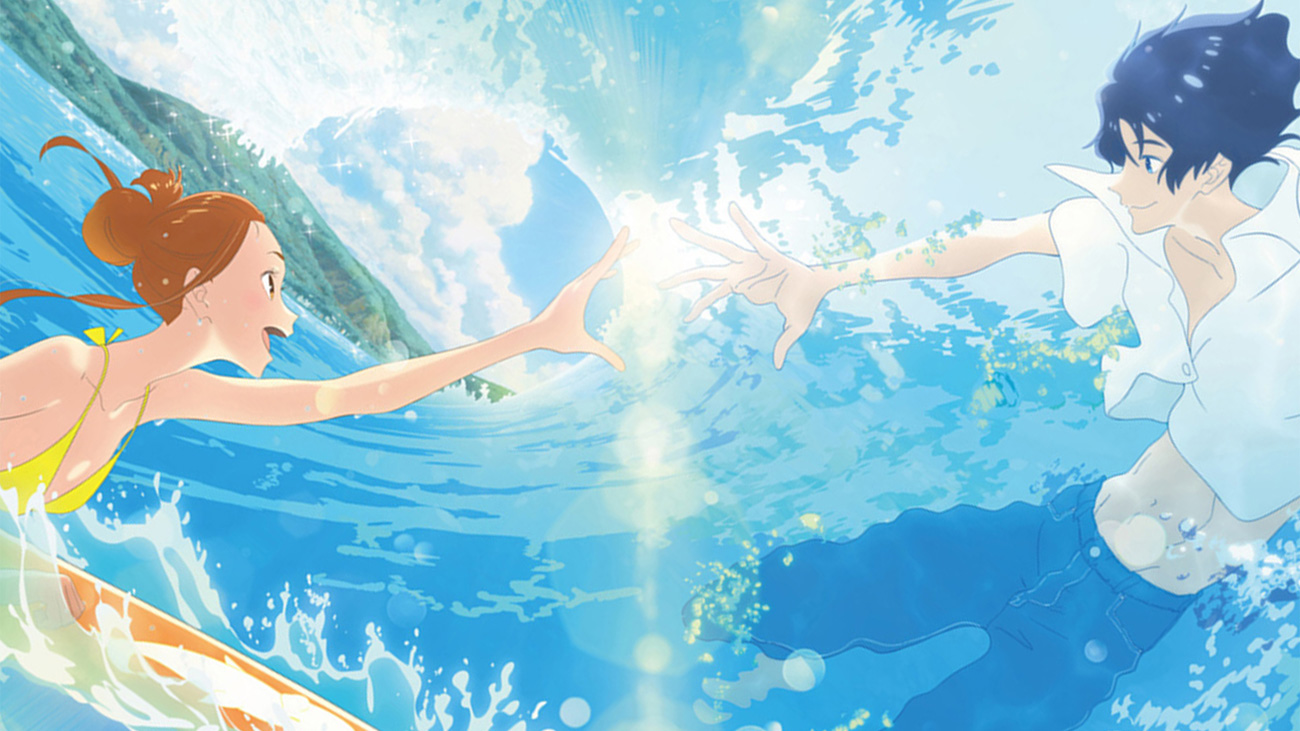

Still from ‘Ride Your Wave’, Yuasa’s newest film screening at JFF 2019.

Science Saru, a return to features & commercial recognition

In 2013, Yuasa co-founded his own studio, Science Saru (whose mascot is the monkey seen in Kemonozume). The studio’s first two projects were the first two films Yuasa had directed since Mind Game: Night is Short, Walk on Girl, a spiritual sequel to The Tatami Galaxy, as it is based on a novel by the writer Tomihiko Morimori (and Yuasa bringing in much of the staff that worked on Galaxy), and Lu Over the Wall, which both released in the span of six weeks in 2017. The latter especially presented the unpredictable auteur an opportunity to go in a new, more accessible direction.

Speaking to Animation World Magazine, Yuasa expressed that even though he was grateful for all the acclaim he had gotten through the years, he wanted to make something that a commercial audience would enjoy.

“I must confess that I’d like to find more supporters and sympathizers and to make a commercial success. I really want to catch up with what people really want.”

With Lu Over the Wall, a film about a lonely teenager named Kai who meets an adorable, candy coloured haired mermaid named Lu, it appeared that Yuasa had finally made something for the average viewer.

The character designs in Lu were more in line with what audiences expected anime to look like and its story was much sweeter and gentler than what was expected from Yuasa. Yet despite Lu’s approachability, Yuasa doesn’t do a complete 180.

The beach dance sequence in Lu, where the little mermaid makes seemingly everyone in Kai’s beach town dance, their feet resembling rubber hoses, calls back to the psychedelic, energetic dance scene in Mind Game. Similarly, the storyline of two individuals from different species wanting to connect with one another also calls back to Kemonozume. And while the shifts in animation are not as drastic in Lu as they are in Yuasa’s debut, they are still noticeable and a clear indication that even though it appeared that Yuasa was trying to soften his approach to anime, Lu is still, unmistakably, a Yuasa film.

Still from ‘Night is Short, Walk on Girl’.

Sadly, Lu was not a success, not even reaching the top 100 films in Japan that year (Night is Short only reached 97). However, just a few months later, Yuasa would finally get that commercial success he had been wanting for so long in a series that wasn’t cute, or gentle, or touching — just pure Yuasa.

Devilman Crybaby was the latest adaptation of the ‘Devilman’ manga series created by Go Nagai and distributed on Netflix. It is a bloody, gory, perverted, apocalyptic, and glorious series that shook up the animation world when it was released on the first week of January 2018. People proclaimed it the series of the year in the calendar year’s first seven days. While tackling a property with a history that dates back to the 1970s, Yuasa, as he does, put his own spin on the series by making it looser and more emotional than older versions of the story; all while maintaining its intense violence.

One aspect of the series that helped it gain momentum thanks to the rise of YouTube and social media were elements of the series’ soundtrack: a mixture of intense, fierce freestyle rapping, and thunderous, dark, and sometimes booming electronic music. All of it was used for the currency of the Internet: memes.

Yuasa’s love and playful use of music can be traced back to his appreciation of the 1968 animated musical Yellow Submarine, and can first be seen in some of his earliest work for Asia-dō. From the jazzy soundtrack that accompanies Kemonozume, to the intense rock song featured in the opening animation of Ping Pong, Yuasa’s use of music to further the mood of his stories and characters is only rivalled by Shinichiro Watanabe and is comparable to how American film directors like Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino use music in their live-action films.

Ride Your Wave seems to be more in line with Lu Over the Wall, with its more accessible visual style and softer tone. For the first time, Yuasa is directing a project where he only directs, the script was solely written by K-ON: The Movie and Liz and the Blue Bird screenwriter Reiko Yoshida. Even with Yuasa being uncharacteristically hands off this time around, Wave has everything you’d expect from a Yuasa feature: lovely visuals, lots of movement, glorious use of colours and music, and characters who have to work on themselves and overcome physical and emotional barriers to grow as people so that they can be free to be themselves and live the life they want to live.

Up next for Yuasa is another Netflix series in 2020, Japan Sinks!, based on Sakyo Komatsu’s 1973 science-fiction novel of the same name. Almost 40 years in the industry, much of that time being one of the most respected voices and visionaries animation has to offer, Yuasa seems to be finally getting the commercial recognition that has long eluded him.

Tex Avery once said that in “cartoons, you can do anything,” and for the past 15 years, no one in animation has taken that message to heart as much as Masaaki Yuasa.